by Amy Lemley

Call it unfinished business.

For Charlottesville photographer Bill Emory, making pictures is an exploration without end. At least so far.

In a characteristically understated "optional statement" about his work, on view at Second Street Gallery through the end of this month, Emory asks simply, "What is the common thread? For a while, we are quick, for another while dead. I've sought redemption trapping light. It hasn't worked yet. I believe it will."

So he continues making pictures, as he has for 27 years, ever since his mother gave him a camera in hope of distracting him, he says, from certain delinquency and an electric bass guitar.

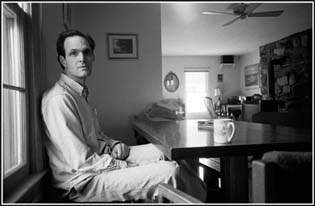

Sitting in the living room of his East Market Street home in Charlottesville's Woolen Mills neighborhood, Emory speaks deliberately, though not without humor, about what moves him to point and shoot.

"It's hard to explain the transformation that people will force to occur on a picture," he says. "This picture, for example, is just another stupid ice scene. But having the people in it"- two children who seem almost enchanted by their surroundings- "makes it work." True enough, but there is more to Emory's innate sense of subject and composition.

As April, his black retriever, dozes nearby, talk turns to his twin daughters, now 12, who are frequent subjects of his work. The room is filled with evidence of their recent past, cast-off stuffed animals above the couch, a shelf of what Emory calls "creepy babies," dirty, forgotten dolls his girls no longer want. "As a parent, you act as an archiving service," he says, smiling.

In art, as in life, it seems, he plays this role, documenting fragments of reality and moments of imagination, often in the same frame. His black-and-white images are at once spontaneous and carefully imagined, glances and good, long looks- at the world, at our neighbors, at ourselves. For Second Street's two-person show, which also features noted photographer Pamela de Marris. Emory chose to pair seemingly unrelated images together in a double mat. "I have a little bit of a problem with the way photographs are traditionally displayed," Emory says in the easy drawl of a native Richmonder. "At first I was going to do what I do personally, with basically big scrapbook pages on the wall. But I kept on chickening further and further out." In the end, he went back to the plain white mat, coupling various images until he made an arrangement he was unwilling to change.

|

|

|

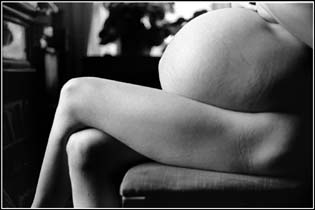

The result is sometimes disturbing, occasionally touching, and always intriguing, inviting the viewer to play with possible relationships between, say, a somber image of a man in a diner booth and a hugely pregnant nude torso with legs crossed. "Both of these people are waiting," he explains, adding quickly that he would just as soon leave the connections up to the viewers.

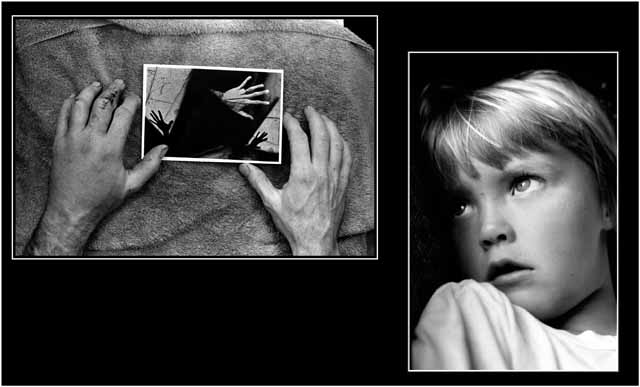

Another pair, Damage and Emma, offer curiously diametric perspectives. In the first image, Emory examines his own left hand, crushed in a workplace accident at a car repair shop: We see the good hand and bad hand holding a photograph of hands. In the second image, a child's face looks bright-eyed and wondrous, hopeful, decidedly undamaged. Viewers find connections where they will.

In his work, Emory seems to rely more on subject matter than elaborate equipment and staging, using mostly natural light and a 21mm Super Angulon wide-angle lens. He points to a photograph from Christmas morning, a pre-presents bribe extracted from his daughters, in which the girls are sprawled on the floor in Mardi Gras masks, with more masks set between them. The result is an eerie crowd scene that nonetheless suggests the kind of happy mayhem that must pervade their time together.

Readers of C-ville Weekly may remember the countless images of the girls and their friends that graced the tabloid's pages a few years back, when Emory was a regular contributor, he focused his lens in other directions, too, but for editor Hawes Spencer the adventures of the group he dubbed the Millmont Gang are Emory's shining moments.

"Bill's greatest subjects are his twin daughters," Spencer says. "They convey intelligence and mystery and 20 other things, and I think it's no accident that they're his. If you know Bill, you know he is a brilliant guy whose last job was as a car mechanic. He's now studying to be a lab technician, but he is probably smarter than most of the doctors at UVa"

Emory, who received a degree in anthropology from the University of Virginia in 1975, also has worked sporadically as a newspaper photographer (his resume lists several Florida newspapers and a two-day stint, "6/15/81-6/17/81" at The Daily Progress).

An interest in helping people led him to this career change, which will make him "a beginner at age 42," he says. That radiography is a type of image-making is secondary.

"There are a thousand rules" for making x-rays, he says, and only one right way to do things. Photography has its rules too, he explained at a January 6 pre-opening gallery talk, and the main ones he tries to remember are to put film in the camera, to remove the lens cap, and to get his subjects' permission. And there's one more: "don't take pictures of children throwing snowballs." As for the other rules? "Don't learn them."

Still, despite efforts at being the antithesis of the intellectual photographer- for the most part, he is self-trained, and the large format photography books he gets as gifts sit eschewed and unopened on a bookshelves- Emory has managed to learn the rules, mastering dark and light, focus and blur, artifice and whim.

What's more, people are starting to notice.

It was both the visual appeal and the sense of narrative in Emory's works that captured the attention of Second Street Gallery director Sarah Sargent.

Sargent compares his photographs to those of Sally Mann, a photographer known for her "compelling immediacy" and who, like Emory, often uses her children as subjects.

"Both their photographs present real subjects as they appear at any given moment during the course of the day, and not prettied-up and posed," Sargent says. (Mann, who serves on Second Street's advisory board, traveled here from Lexington to meet with Emory and view the exhibition last weekend.)

With just 10 exhibitions per year and more than 350 applicants from across the country hoping to fill them, competition for a Second Street Gallery show is tough. Cited by the National Endowment for the Arts in 1991 as a "model outpost gallery," offering urban-caliber programming in a nonurban setting, Second Street is a recognized showcase for new and emerging American artists. Perhaps it's only fitting, then, that this artist, by his own admission still emerging, still seeking redemption, is there to kick off the New Year.

"Promise and potential reside on film in my camera," Emory told visitors during his gallery talk. "My anticipation builds, as I work through a roll. I'm gripped by the hope that intention, beauty, and ineffable wonder will soon be made manifest." Borrow this hope when you visit Second Street Gallery; it may well be realized.

Amy Lemley

The Observer 1/26/95